History of Christian Missions to China

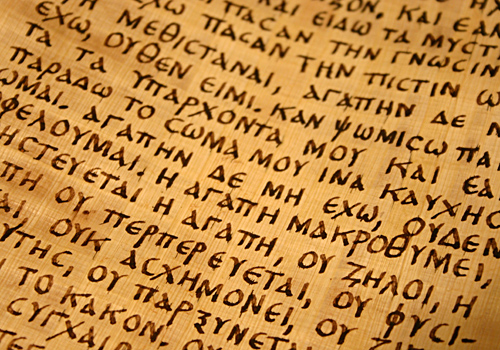

Therefore go, and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit. Matthew 28:19

The stories of Christian missionaries are an inspiration to all Christians, and highlights their dedication to spreading the gospel — often at extreme personal cost. This page outlines some of the history of Christianity in China, from its earliest days, to having one of the largest Christian populations in the world today.

I first became interested in Christianity in China when I read the book "The Heavenly Man" by Brother Yun and Paul Hattaway. It was around the time I became a Christian, near the end of the first decade of the 2000s. Reading it helped me want to be a Christian myself. Yun's story, and especially his positive, humble, and loving attitude — while in situations of incredible physical suffering — is one of the most inspiring things I've ever read in my life.

Along with similar stories of other persecuted Christians (including those in the Bible), the testimonies of these faithful Christians have been among the greatest comforts I've ever known in times of distress. And make the problems of my own life seem trivial in comparison. Even just the story of how Yun gets his first Bible is amazing, and changed the way I thought about the Bible myself — making it feel even more sacred and precious.

The Great Commission that Jesus gave us at the end of Matthew 28 tells us to go out to "all nations" spreading the good news of the gospel of Christ. Missionary work is often dangerous — and in the past it was often even more risky than it is today. In our modern era of comparatively very safe worldwide travel, it’s sobering to remember the difficulties of travel in ancient times:

In the early days of wind-powered sailing ships (including when Christianity first spread), travel was an extremely risky undertaking. Out of 376 Jesuit missionaries to China that sailed between 1581 and 1712, 127 of them (almost exactly one-third) died on the way there. This demonstrates some of the amazing dedication of many Christian missionaries, and their eagerness to tell the world about Jesus, regardless of the (earthly) cost to themselves.

This page is taken from an assessment task for a Church History subject I did last year, and therefore it reads more technically than the other pages on this website so far. If I get time sometime, I might go over it and make it read a bit friendlier...

Abstract

The historic balance between foreign missionary activity and localised Christianity (i.e. indigenisation) in China is discussed. Before the twentieth century, there were several waves of foreign missionary activity into China. The first few of these led to conversions and the growth of Christianity — which was then later eliminated due to persecution and lack of political acceptance. During some of these periods there is evidence for indigenisation beginning to develop. However, it was stamped out in the next wave of persecution.

This situation reversed shortly after 1900. The Boxer Rebellion, which sought to remove Christianity from China, had the opposite effect as in its wake the Chinese government encouraged more Western missionary activity. This encouragement was met with a massive response by Western missionaries to evangelise, and also to intentionally promote the indigenisation of Christianity in China. After this, Chinese Christianity was able to survive and grow of its own accord during the Communist period when foreign missionary activity into China was banned. Since then, this indigenised Chinese Christianity has continued to prosper and to grow dramatically.

Introduction

The story of Christianity in China began with missionaries. Someone had to travel to China to bring the gospel of Jesus and preach it (Romans 10:14) so Christianity could be established there. But once established, did China’s Christianity become independent of its roots in ongoing foreign missionary activity? And if so, exactly when did this happen? This essay discusses the establishment and growth of China’s own independent, indigenised, Christianity over nearly fourteen centuries.

The history of Christianity in China has been a long series of waves of acceptance and expansion, followed by persecution. Each period of persecution caused a decline (or a complete elimination) of Christianity in China until the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. During this period Western nations made China the focus of their missionary work, which reached its all-time peak around 1910. Thanks to such a massive influx of missionaries, China’s Christianity was finally able to become independent. The final, successful transition from missionary era Christianity to indigenous Christianity was accomplished gradually, and was more of a collaboration than entirely from the efforts of Chinese Christians. But once accomplished, China has not only retained but dramatically grown its population of Christians — even during Mao’s years when persecution was intense and foreign missions were completely forbidden.

Part 1 — Christianity in China before 1900

Before 1900 there were many attempts to bring Christianity into China. The earlier attempts ended in failure due to Imperial bans and persecution. Indigenisation that may have occurred after each of these initial missionary efforts was erased, and the whole process had to start over again with later missions.

The First Missionaries to China from 635 A.D.

Apart from vague claims about the Apostle Thomas, the earliest known Christianity in China was introduced by Nestorian missionaries. In the year 1625,1 the Nestorian Stele was discovered,2 documenting Christian missionaries arriving in China in A.D. 635.3 Because records are so few, it’s hard to evaluate the indigenisation of China’s Nestorian Christianity. Thompson says historians believe the Chinese “Nestorian” church did not follow the controversial Christology of Nestorius.4 This would suggest they had changed from the beliefs of their founders, and therefore perhaps had become somewhat indigenised.5

To whatever extent this church had become established, it did not last very long. In the ninth century Christianity6 was banned by the Chinese government. This was so thorough that a visiting monk in 980 said he could only find one Christian in the whole of China.7 Cooper writes of a Christian monk in Baghdad who said in 987, “There is not a single Christian left in China.”8

The Second Wave of Missionaries to China

Lieu states that Nestorianism was reintroduced into China in the thirteenth century by Mongols, but it did not win many converts.9 It’s possible that the Mongols (some tribes of whom were Nestorians) were originally converted by the Chinese Nestorians before they were supressed.10 Shelley states that at the beginning of the fourteenth century, the Asian Nestorian church has ten major churches and numerous native clergymen.11

There were also Franciscan missionaries sent to the East around this time.12 Dawson paints a more successful picture of Christian mission work in China in this period than does Lieu, stating that an archbishopric was established in 1275 at Peking, and churches were founded by Christian officials and merchants in many of the principal cities of China.13 This discrepancy would be resolved if the Mongol Nestorians did not win many converts, but the Franciscan missionaries did. In any case, a further wave of persecution against Christianity began around the mid-1300s and was successful in eliminating Christianity entirely (or at best, almost entirely) from China. Dawson states that the last Catholic Bishop of Zaytun14 was martyred in 1362, and Christians were expelled from Peking in 1369. So once again the slate of Chinese Christianity was wiped blank.

Jesuit Missionaries Enter China in the late 1500s

The next wave of missionaries to China began with the Jesuits.15 Francis Xavier did not make it to China, though he paved the way for other Jesuits.16 Matthew Ricci was first to enter China, and settled in Peking for 10 years.17 On Ricci’s death there were about 2000 Chinese Christians. His successor, Adam Schall18 grew that number to almost 270,000.19 However, the Christianity that eventuated from their missionary work was not approved of by the Church of Rome. Interestingly, this was because it was viewed as too indigenised.20

Protestant Missions to China

The first Protestant missionary to China was Robert Morrison, arriving in 1807.21 Like their Catholic predecessors, the missionaries of the 1800s faced great hardships.22

Illness and death (including sometimes even from suicide) was a characteristic feature.23 There were also other difficulties such as monetary cost of travel and living costs, and the difficulty of learning the language. Lutz comments that Westerners originally thought that their missionaries would convert a few Chinese, who would then spread the gospel to all of China — but this did not happen.24 At least not in the lifetimes of these missionaries. Over 100 years later, China has one of the largest Christian populations in the world, and by 2030 it may have the largest.25

Two Protestant missionaries who would have great influence on future missionary work both arrived in China in the same year, 1854.26 John Livingstone Nevius (1829-1893) stayed in China three decades and espoused different methods from previous foreign missionaries. He promoted motivating locals to evangelise their own people,27 mostly without external financial input,28 and to form self-governing churches.29 All these were forms of indigenisation, though they did not initially catch on in China as Nevius had hoped.30 He wrote several influential books, including one on demon possession.31 Hudson Taylor settled in coastal Shanghai and Ningbo for the first few years,32 and then later went inland. In 1865, Taylor established the China Inland Mission and wrote the hugely influential book “China’s Spiritual Needs and Claims”.33 Taylor’s influence was so immense that historian Ruth Tucker said “No other missionary in the nineteen centuries since the Apostle Paul has had a wider vision and has carried out a more systematised plan of evangelising a broad geographical area than Hudson Taylor.”34

Part 2 — Christianity in China during 1900-1949

The Boxer Rebellion of 1900, though it did cause some missionaries to leave China, did little to slow missionary efforts towards China, nor the growth of Chinese Christianity. In fact, it had the opposite effect. In the wake of the Boxer Uprising, the Chinese government initiated Christian-friendly reforms, and the church faced much less hostility overall than it had in the nineteenth century.35 Graves states that in 1903 there were 67 missionary societies operating in China,36 and much of the progress was made after the Boxer Uprising.37

Totire says that originally missionaries did the preaching, but it was soon evident that Chinese converts needed to be trained for this work, because the Chinese were more receptive hearing their own people. He explains how Dr Lewis C. Hylbert deliberately trained and encouraged the Chinese to teach and lead and take over the missionaries’ work. This began around the 1910s.38 Totire concludes by commenting on how deliberate indigenisation allowed Chinese churches to continue during the periods when foreign missionaries’ activity was restricted.39

According to Clark, there were three stages of progress from the missionary era in China to the indigenous era. The first era imagined a culturally and religiously transformed China. The second era was based on missionaries adjusting and acclimatising to Chinese society. In the third era, missionaries actively advocated for a locally empowered (indigenous) Christianity in China.40 Clark’s first two eras correspond to the periods up to and including the nineteenth century. His third era is more like the missions that Totire describes as beginning in the 1910s. Tiedemann describes a similar expansion in Chinese Pentecostalism from about 1910 onward.41

An interesting aspect of how China’s Christianity begins to indigenise around this time is found in comments from historians such as Dr Gloria Tseng42 about how literally the Chinese interpreted the gospel message and the Bible overall. The preachers John Sung and Wang Mingdao are examples of this. This contrasts the trend in the West at the time, which was towards viewing the gospel more as a metaphor, with a decline in the literal belief in many of the supernatural aspects of Christianity. 43

Tseng then says that the anti-Christian Northern Expedition44 caused an exodus of foreign missionaries in China, and the high point in missionary activity after the Boxer Rebellion was never again reached. Then, surprisingly, there was a wave of revival during the late 1920s through the 30s. This revival was brought by homegrown Chinese Christian leaders such as Sung and Mingdao. This is where China’s Christianity does appear to become truly indigenised, as for the first time its continuation and growth arise from within China itself. Tseng states that these preachers “Indigenised the Chinese church by reviving it, without ever making ‘indigenisation of the Chinese church’ an issue in either their sermons or their writings.” 45

Tseng states that Sung and Mingdao not only had no formal theological training, but that their “strong suspicion against Western theological training was to be a feature of the indigenization of Christianity in Republican China.”46 She highlights the Bible as the focus of Chinese Christianity and its indigenisation.47 Her description of the Chinese viewing the Western missionaries as lukewarm seemingly contradicts the spirit of the earlier Western missionaries and their great sacrifices. Perhaps this “devolution” in the piety of Western missionaries (either real, or at least perceived that way by the Chinese) was a factor leading to China developing its own indigenised Christianity.

Part 3 — Christianity in China, 1949 to 1976

In 1949 China became a Communist nation under Chairman Mao Zedong. Foreign missionaries were ordered to leave. By 1952 there were only twenty-one missionaries left in Communist China awaiting expulsion.48 Hughes Old states that things happen because of God, not because of people.49 While God is clearly in control overall, it is also true that for a church to exist, God must work through people. And in the period following 1949, these people were the Chinese nationals who had made Christianity their own in the previous decades.

One feature of this period (and which remains today) was the split of the Chinese Christian church into two different streams, the registered churches and the unregistered churches.50 These streams demonstrate the process of indigenisation operating in two extremely different ways. Interestingly, Chinese Communism has itself been described as indigenous, because of its differences with other communist regimes (notably the USSR) and its closed foreign relations policy.51 Given China’s long history of individuality and separation from the rest of the world, a high degree of indigenisation within China (including Chinese Christianity) should be little surprise.

Part 4 — Christianity in China Since 1976

In 1976 Chairman Mao died, ending the Cultural Revolution and its intense persecution.52 New leaders, such as Deng Xiaoping, were less harsh with Christianity and with closing China to the West.53 Along with the reopening came information about what had happened to Christianity. Mao had expected religion to die a natural death — however Chinese Christianity had not only survived but had grown tremendously.54 The Protestant Church had grown from 1 million to 3 million (while the Catholic Church stayed the same at about 3 million).55

Since 1976, Christianity in China has grown even more dramatically.56 Kaiser gives figures of 700,000 Protestants in 1959; 1.5 million in 1976; 3 million in 1982; 6.7 million in 1986; 9.4 million in 1992; and 16.7 million in 1998. For 2014 he quotes 24 million in the TSPM plus an estimated 45-70 million in about 300 unofficial house church networks, plus 6 million official and 6-8 million unofficial Catholics.57 Giving a total today of about 90 million Christians in China — perhaps more.58

Cao says that since the 1990s a new type of “boss Christians” have emerged and spearheaded local church development.59 Many Chinese Christians (both young and old) are still unimpressed by the TSPM church.60 Clark makes the point that Christianity in China is complex and varied.61 Recent years bring both good and bad news. There are optimistic plans for China to send many missionaries to other countries.62 During 2018, a new wave of severe persecution and tightening of government restrictions on Chinese Christian activities began.63 The effects of this on the future of Christianity in China remain to be seen.

Conclusion

Before 1900, there were several periods of missionary activity interspersed with periods of persecution which effectively ended Christianity in China. Indigenisation was interrupted and delayed. There’s evidence for some indigenisation of those pre-1900 groups. It’s not that Chinese Christianity before 1900 never became independent — but whatever had become developed was then erased in the next wave of persecution.

However, persecution in the 1900s gave different results. Shortly after the Boxer Rebellion was the all-time high of missionary activity, along with deliberate efforts to help Christianity in China become independent of the West. Thanks to this, Christianity in China built up enough momentum to survive and grow independently under the Communist persecutions. This has been so successful that by the year 2030, China may have the largest Christian population of any country in the world.

Footnotes

1 Thompson states the year of discovery as 1623, and the year the text was published as 1625. Keevak gives 1625 as the date of discovery of the stele. Glen L. Thompson, "Christ on the Silk Road," Touchstone: A Journal of Mere Christianity 20, no. 3 (2007): 31.

2 A huge black tablet about 3 metres high and a metre wide was unearthed in northwestern China. It became known as the Nestorian Stele. Michael Keevak, The Story of a Stele: China's Nestorian Monument and Its Reception in the West, 1625-1916 (Aberdeen, Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2008), 5.

3 Its inscribed text says it was written on Sunday, February 4, 781 A.D., and that in 638 the Emperor decreed the Christian teaching as helpful and beneficial and is to have free course throughout the empire. The authenticity of the Stele was confirmed by the discovery in 1908 of scrolls in a cave in Dunhuang, the oldest of which date back to between 635 and 638 and confirm the Nestorian church in China. Thompson, "Christ on the Silk Road," 31-33.

4 Ibid., 36.

5 Perhaps this change was due to the guidance of the Holy Spirit, since the beliefs of Nestorius himself are generally regarded as aberrant. Shelley, Church History in Plain Language, 120-22.

6 Along with other foreign religions.

7 Samuel N. C. Lieu, "Nestorians and Manichaeans on the South China Coast," Vigiliae christianae 34, no. 1 (1980): 74.

8 Derek Cooper, Introduction to World Christian History (InterVarsity Press, 2016), Chapter 1: Asia.

9 Lieu, "Nestorians and Manichaeans on the South China Coast," 74.

10 Christoph Baumer, The Church of the East: An Illustrated History of Assyrian Christianity (Great Britain: I.B. Tauris, 2006), 169-210. If true, this would be an example of missionary activity (in the seventh century) resulting in indigenisation, which then sent its own missionaries to evangelise the Mongols, who then returned to re-evanglise China (now as missionaries themselves) after the political situation changed. Thus, missionary activity and the development of localised Christian activity are inter-related and interdependent.

11 Shelley, Church History in Plain Language, 121.

12 Christopher Dawson, ed. , The Mongol Mission: Narratives and Letters of the Franciscan Missionaries in Mongolia and China in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries. Translated by a Nun of Stanbrook Abbey. Edited with an Introd. By Christopher Dawson (New York: Sheed and Ward, 1955), xv-xxxv.

13 Ibid., xxvii.

14 Sometimes spelt as Zaiton, and now known as Quanzhou.

15 Shelley refers to Francis Xavier, one of the first seven Jesuits, as “The great pioneer of Christian Missions in the Far East.” Xavier had a commission from the pope and king to evangelise the entire Far East. He first went to India, the Malaya, then Japan, and died before arriving in China. Shelley, Church History in Plain Language, 297-301.

16 In the modern era of air travel, it’s sobering to remember the difficulties of travel in ancient times. In the early days of wind-powered sailing ships (including when Christianity first spread), travel was an extremely risky undertaking. Out of 376 Jesuit missionaries to China that sailed between 1581 and 1712, 127 of them (almost exactly one-third) died on the way there. This demonstrates some of the degree of dedication of the early missionaries. Ibid., 295.

17 Ricci’s Western education in mathematics, astronomy, and cosmology was of great help as the Chinese were impressed by and interested in his learning.

18 Also known as Johann Adam Schall von Bell, and by his Chinese name Tang Ruowang.

19 Schall also gained freedom for Christianity in all of China. Shelley, Church History in Plain Language, 301.

20 The Chinese Christians equated their original “Lord of Heaven” with the Christian God, and had adapted some of their original practices (such as ancestor worship) to Christianity rather than discarding them. This then led to internal conflict and a decline in missionary activity. Ibid.

21 Christopher A. Daily, Robert Morrison and the Protestant Plan for China, Royal Asiatic Society Books (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2013), Book, 2.

22 John Livingston Nevius, The Planting and Development of Missionary Churches, 3rd ed. (New York: Foreign Mission Library, 1899), 45.

23 As examples, Helen Nevius gives an account of the death at sea of the Hon. Walter Lowrie, at the hands of pirates. Helen Sanford Nevius, Our Life in China, Travel and Adventure Series (New York,: R. Carter, 1869), 28-30. Hudson Taylor’s residence in Ningbo had a rope tied to an upper storey window in case they needed to escape quickly from attackers. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Windowjump.jpg

24 Jessie Gregory Lutz, "Attrition among Protestant Missionaries in China, 1807-1890," International Bulletin of Missionary Research 36, no. 1 (2012): 23.

25 Michael Ryan, "The Church in China and Lessons from the Cold War," America 218, no. 13 (2018): 10.

26 Nevius, Our Life in China, 8,11-14. Howard and Taylor Taylor, Howard, Mrs., Hudson Taylor in Early Years: The Growth of a Soul (New York, Philadelphia: The China Inland Mission, 1912), 201-03.

27 Nevius, The Planting and Development of Missionary Churches, 41.

28 Ibid., 42-44.

29 Ibid., 58-60.

30 Nevius later travelled to Korea and his method, which became known as the “Nevius Plan”, was extremely successful there. Everett N. Hunt, Jr., "The Legacy of John Livingston Nevius," International Bulletin of Missionary Research 15, no. 3 (1991): 124.

31 John Livingston Nevius, Demon Possession and Allied Themes; Being an Inductive Study of Phenomena of Our Own Times (Chicago,: F.H. Revell company, 1895).

32 Taylor, Hudson Taylor in Early Years: The Growth of a Soul.

33 James Hudson Taylor, China; Its Spiritual Need and Claims; with Brief Notices of Missionary Effort, Past and Present (London: James Nisbet, 1865). The creation of this book and the beginnings of the China Inland Mission are described in Howard and Taylor Taylor, Howard, Mrs., Hudson Taylor and the China Inland Mission; the Growth of a Work of God, 4th impression. ed. (London, Philadelphia, Toronto, Melbourne and Shanghai: Morgan & Scott, China Inland Mission, 1920), 33-47.

34 This quote is widely reported on the internet, including on Wikipedia, though in the 2nd edition of her book Tucker softens her comment to “Few missionaries in the nineteen centuries since the Apostle Paul have had a wider vision and have carried out a more systematised plan of evangelising a broad geographical area than did James Hudson Taylor”. Ruth A. Tucker, From Jerusalem to Irian Jaya: A Biographical History of Christian Missions (Grand Rapids, Michagan: Zondervan, 2004), 186.

35 Kevin Xiyi Yao, "At the Turn of the Century: A Study of the China Centenary Missionary Conference of 1907," International Bulletin of Missionary Research 32, no. 2 (2008): 65. Also Gloria S. Tseng, "Revival Preaching and the Indigenization of Christianity in Republican China," ibid.38, no. 4 (2014): 177.

36 Plus three Bible Societies and a few other Christian charitable societies.

37 Graves quotes a missionary who said to a Chinese statesman “You cannot suppress Christianity. For every missionary you kill, two will be sent out. For every chapel you destroy two more will be opened.” R. H. Graves, "The Present Missionary Situation in China," Review & Expositor 2, no. 1 (1905): 83-84.

38 Alan Totire, "Dr. Lewis C. Hylbert and the Indigenization of the East China Baptist Mission," American Baptist Quarterly 28, no. 4 (2009): 407-08.

39 For example the Japanese invasion of World War II, and especially the final expulsion of foreign missionaries that began in 1949. Ibid., 411.

40 Clark, China's Christianity: From Missionary to Indigenous Church, 7.

41 R. G. Tiedemann, "The Origins and Organizational Developments of the Pentecostal Missionary Enterprise in China," Asian Journal of Pentecostal Studies 14, no. 1 (2011): 130.

42 Dr. Gloria Tseng is Associate Professor of History at Hope College, Michagan.

43 Tseng, "Revival Preaching and the Indigenization of Christianity in Republican China," 177-82.

44 An internal military campaign from 1926 to 1928, aimed at reunifying China.

45 Tseng, "Revival Preaching and the Indigenization of Christianity in Republican China," 177.

46 Ibid., 177-78. Tseng goes on to say that “Sung's one semester at Union Theological Seminary in New York after receiving his Ph.D. degree served as theological preparation only in a negative sense—he saw what not to preach. What the two men shared was a period of prolonged and intense personal study of Scripture—reading through the entire Bible numerous times-before the start of their nationwide preaching ministries. Both also maintained a lifelong discipline of regular Bible reading and prayer in personal devotions. Unsurprisingly, the Bible was central to both men's preaching and teaching throughout their lives. More than one hundred years after the London Missionary Society's Robert Morrison had completed his translation of the Bible into Chinese, the Bible was finally appropriated by Chinese Christians as their own book.”

47 Tseng then says that “In the end, the greatest debt owed by Chinese Christians to Western missionaries was the Bible; when the Bible became a Chinese book, Christianity also became Chinese. Even when Chinese Christians rejected what they perceived to be the lukewarm or even decadent mission churches of their day, they embraced the faith by embracing the book.” Ibid., 182.

48 “China has long been the foremost field of North American foreign missionary endeavour, at least from the viewpoint of the number of missionaries and the amount of money allocated to any one country. The expulsion of missionaries and the prohibition by the present Chinese Government of the reception of foreign funds by Christian churches and institutions have completely altered this situation. Once 33 per cent of all Protestant missionaries from the United States and Canada were stationed in China… Only twenty-one missionaries still remain in Communist China awaiting expulsion.” R. Pierce Beaver, "A Report on the Reallocation of China Missionaries and Funds by North American Mission Boards," Occasional Bulletin 3, no. 14 (1952): 1.

49 He says that “By the end of the 1940s, all hope of a Chinese Christian church would be given up. The work of the missionaries had been completely overturned. Only God could give China a church… In the history of salvation, God’s election makes all the difference.” Hughes Oliphant Old, The Reading and Preaching of the Scriptures in the Worship of the Christian Church, Vol. 7: Our Own Time (Grand Rapids, Michagan: Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2010), 619.

50 The only government-recognised Protestant church in China is known as the “Three-Self Patriotic Movement”, or TSPM.

51 Arthur F. Glasser, "Timeless Lessons from the Western Missionary Penetration of China," Missiology 1, no. 4 (1973): 462.

52 The last ten years of Mao’s rule, from 1966-76, were known as the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution. The aim was to end all religion in China, and even the official churches were persecuted during this period. Shelley, Church History in Plain Language, 508.

53 Brother Yun and Paul Hattaway, The Heavenly Man : The Remarkable True Story of Chinese Christian Brother Yun (London: Monarch, 2002), 8.

54 H.O. Old, The Reading and Preaching of the Scriptures in the Worship of the Christian Church, Vol. 7: Our Own Time (Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2010), 611.

55 Kathleen L. Lodwick, How Christianity Came to China: A Brief History (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2016), xv.

56 Fulton says that in 2007 there were slightly over 60 million Christians in China, and the growth has been in both rural and urban areas. Brent Fulton, China's Urban Christians : A Light That Cannot Be Hidden (Cambridge, United Kingdom: The Lutterworth Press, 2016), Book, 2.

57 Sigurd Kaiser, "Church Growth in China: Some Observations from an Ecumenical Perespective," The Ecumenical Review 67, no. 1 (2015): 36.

58 Kaiser also says the majority are older people, mainly women, in rural areas. Ibid., 37.

59 This seems very much like the “prosperity gospel” style of Western Christianity. Earlier we saw the piety of native Chinese preachers in contrast to “hedonistic” Western Christians in the 1930s and 40s as an example of indigenisation. Now, after Chinese Christianity has had decades to grow and develop within itself, part of it appears to be paralleling some Western trends towards materialism. However this seems to be more an indigenous feature coming from within China (as many modern Chinese are very materialistic) than something being brought in by missionaries. Nanlai Cao, Constructing China's Jerusalem: Christians, Power, and Place in Contemporary Wenzhou (Stanford University Press, 2010), The beginning of Chapter 4.

60 Cao says that many elderly churchgoers still see TSPM as a tool of the state and a betrayer of the faith. And that some younger believers believe that TSPM churchgoers are unsaved. Ibid., page unknown.

61 Clark says that to ask what China’s Christianity is like would be akin to asking what American Christianity is like. Clark, China's Christianity: From Missionary to Indigenous Church, 12.

62 “They announced from Hong Kong a long-discussed goal: to send 20,000 missionaries from China by the year 2030. The number is enormous, especially for a country that has sent only a few hundred foreign missionaries so far.” Sarah Eekhoff Zylstra, "Made in China: The Next Mass Missionary Movement," Christianity Today 60, no. 1 (2016): 20.

63 Associated Press; Christian Century Staff, "China Continues Efforts to Exert Party Control over Religious Groups," Christian Century 135, no. 21 (2018); Diana Chandler, "A Return to Mao Era Persecution in China?," Accessed October 4, 2018, http://www.bpnews.net/51700/a-return-to-mao-era-persecution-in-china; Eugene, "China Drafts New Law against Christians Messaging Each Other," Accessed October 4, 2018, https://backtojerusalem.com/china-drafts-new-law-against-christians-messaging-each-other/.

Bibliography

Andrew, John L. Sherrill, and Elizabeth Sherrill. God's Smuggler. Expanded Edition. ed. Minneapolis Minnesota: Chosen, 2015.

Baumer, Christoph. The Church of the East: An Illustrated History of Assyrian Christianity. Great Britain: I.B. Tauris, 2006.

Beaver, R. Pierce. "A Report on the Reallocation of China Missionaries and Funds by North American Mission Boards." Occasional Bulletin 3, no. 14 (1952): 1-6.

Cao, Nanlai. Constructing China's Jerusalem: Christians, Power, and Place in Contemporary Wenzhou. Stanford University Press, 2010.

Chandler, Diana. "A Return to Mao Era Persecution in China?" Accessed October 4, 2018, http://www.bpnews.net/51700/a-return-to-mao-era-persecution-in-china.

Clark, Anthony E. China's Christianity: From Missionary to Indigenous Church. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2017.

Cooper, Derek. Introduction to World Christian History. InterVarsity Press, 2016.

Daily, Christopher A. Robert Morrison and the Protestant Plan for China. [in English] Royal Asiatic Society Books. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2013. Book.

Dawson, Christopher, ed. . The Mongol Mission: Narratives and Letters of the Franciscan Missionaries in Mongolia and China in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries. Translated by a Nun of Stanbrook Abbey. Edited with an Introd. By Christopher Dawson. New York: Sheed and Ward, 1955.

Eekhoff Zylstra, Sarah. "Made in China: The Next Mass Missionary Movement." Christianity Today 60, no. 1 (2016): 20-21.

Eugene. "China Drafts New Law against Christians Messaging Each Other." Accessed October 4, 2018, https://backtojerusalem.com/china-drafts-new-law-against-christians-messaging-each-other/.

Fulton, Brent. China's Urban Christians : A Light That Cannot Be Hidden. [in English] Cambridge, United Kingdom: The Lutterworth Press, 2016. Book.

Glasser, Arthur F. "Timeless Lessons from the Western Missionary Penetration of China." Missiology 1, no. 4 (1973): 445-64.

Graves, R. H. "The Present Missionary Situation in China." Review & Expositor 2, no. 1 (1905): 80-93.

Hunt, Everett N., Jr. "The Legacy of John Livingston Nevius." International Bulletin of Missionary Research 15, no. 3 (1991): 120.

Kaiser, Sigurd. "Church Growth in China: Some Observations from an Ecumenical Perespective." The Ecumenical Review 67, no. 1 (2015): 35-47.

Keevak, Michael. The Story of a Stele: China's Nestorian Monument and Its Reception in the West, 1625-1916. Aberdeen, Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2008.

Lieu, Samuel N. C. "Nestorians and Manichaeans on the South China Coast." Vigiliae christianae 34, no. 1 (1980): 71-88.

Lodwick, Kathleen L. How Christianity Came to China: A Brief History. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2016.

Lutz, Jessie Gregory. "Attrition among Protestant Missionaries in China, 1807-1890." International Bulletin of Missionary Research 36, no. 1 (2012): 22-27.

Nevius, Helen Sanford. Our Life in China. Travel and Adventure Series. New York,: R. Carter, 1869.

Nevius, John Livingston. Demon Possession and Allied Themes; Being an Inductive Study of Phenomena of Our Own Times. Chicago,: F.H. Revell company, 1895.

———. The Planting and Development of Missionary Churches. 3rd ed. New York: Foreign Mission Library, 1899.

Old, H.O. The Reading and Preaching of the Scriptures in the Worship of the Christian Church, Vol. 7: Our Own Time. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2010.

Old, Hughes Oliphant. The Reading and Preaching of the Scriptures in the Worship of the Christian Church, Vol. 7: Our Own Time. Grand Rapids, Michagan: Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2010.

Ryan, Michael. "The Church in China and Lessons from the Cold War." America 218, no. 13 (2018): 10-10.

Shelley, Bruce L. Church History in Plain Language. Updated 4th edition / ed. Nashville, Tennessee: Thomas Nelson, 2013.

Staff, Associated Press; Christian Century. "China Continues Efforts to Exert Party Control over Religious Groups." Christian Century 135, no. 21 (2018): 15-16.

Taylor, Howard and Taylor, Howard, Mrs. Hudson Taylor and the China Inland Mission; the Growth of a Work of God. 4th impression. ed. London, Philadelphia, Toronto, Melbourne and Shanghai: Morgan & Scott, China Inland Mission, 1920.

———. Hudson Taylor in Early Years: The Growth of a Soul. New York, Philadelphia: The China Inland Mission, 1912.

Taylor, James Hudson. China; Its Spiritual Need and Claims; with Brief Notices of Missionary Effort, Past and Present. London: James Nisbet, 1865.

Thompson, Glen L. "Christ on the Silk Road." Touchstone: A Journal of Mere Christianity 20, no. 3 (2007): 30-36.

Tiedemann, R. G. "The Origins and Organizational Developments of the Pentecostal Missionary Enterprise in China." Asian Journal of Pentecostal Studies 14, no. 1 (2011): 108-46.

Totire, Alan. "Dr. Lewis C. Hylbert and the Indigenization of the East China Baptist Mission." American Baptist Quarterly 28, no. 4 (Wint 2009): 407-12.

Tseng, Gloria S. "Revival Preaching and the Indigenization of Christianity in Republican China." International Bulletin of Missionary Research 38, no. 4 (2014): 177.

Tucker, Ruth A. From Jerusalem to Irian Jaya: A Biographical History of Christian Missions. Grand Rapids, Michagan: Zondervan, 2004.

Yao, Kevin Xiyi. "At the Turn of the Century: A Study of the China Centenary Missionary Conference of 1907." International Bulletin of Missionary Research 32, no. 2 (2008): 65.

Yun, Brother, and Paul Hattaway. The Heavenly Man : The Remarkable True Story of Chinese Christian Brother Yun. London: Monarch, 2002.